Burford Capital

A Dominant Niche Player with Significant Optionality (This is not investment advice. Please do your own research)

Executive Summary

Burford Capital Limited (BUR) provides investment capital, asset management, financing, and risk solutions for the legal sector. It serves law firms and corporate litigants around the world. With more than $4 billion committed in litigation assets, it is by far the largest player in this growing niche. Burford has achieved outstanding investment returns, generating 30% IRR since its inception. The size of the total addressable market for litigation finance is not well defined, but it is at least tens of billions, and likely much more. Burford currently offers six types of services: (i) Core litigation finance, (ii) Complex strategies, (iii) Asset management, (iv) Asset recovery, (v) Post settlement, and (vi) Legal risk management.

I believe the Company offers investors an attractive investment opportunity because (1) the market underappreciates the economic moat of Burford Capital; (2) the market is overconcerned about volatility of earnings; and (3) best-in-class management and investment team creates strong interest alignment and potential for long-term value creation.

I recommend a long position in BUR as I believe the intrinsic value of the business is 15-50% above the current valuation.

Company History and Overview

Incorporated in Guernsey, Burford Capital was founded by Christopher Bogart and Jonathan Molot in 2009 to fund legal cases. Initially, BUR was registered as a closed-ended collective investment scheme and was listed on the London AIM Stock Exchange in October 2009, and it issued more shares in a follow-on in 2010. In 2012, BUR underwent a reorganization to implement a new group structure incorporating certain of its wholly owned subsidiaries, acquiring its investment adviser through a cashless merger. In 2019, short seller Muddy Water initiated a public short campaign on Burford. In response to investor feedback, BUR pursued a second listing on the New York Stock Exchange and was successfully listed on the NYSE in Oct 2020.

BUR has made several acquisitions throughout its history to augment its services. In 2011, it paid £10.3 million to acquire Firstassist Legal Expenses Insurance, a leading provider of litigation expenses insurance in the U.K. In 2015, it acquired Focus Intelligence Ltd., a business intelligence firm that specializes in investigative litigation and arbitration, asset tracing, and judgement enforcement. In 2016, it acquired GKC Holdings, a law-focused asset manager registered as an investment adviser with the SEC and parent of Chicago-based Gerchen Keller Capital, for $160 million, adding a third-party asset management business to expand the diversity of its capital offerings.

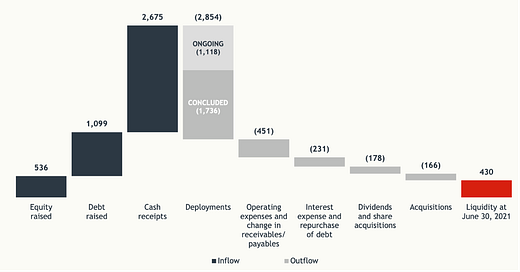

Since its founding, BUR has raised a total of $1.6 billion of capital, $536 million in equity and $1.1 billion in debt. It has generated nearly $2.7 billion in cash receipts. Below is a detailed cash bridge of BUR from its inception to June 30, 2021.

Business Summary and Analysis

Business Mix

Burford Capital has three principal operating segments: (1) Capital provision, (2) Asset management, and (3) Services and other corporate.

For (1), BUR provides capital to clients in its core litigation finance activities. The capital is provided either (a) directly or (b) indirectly. Category (a) includes all its litigation finance assets that BUR has invested directly using capital from its balance sheet. This is the bread and butter of BUR’s business and BUR usually targets risk-adjusted IRRs in the mid-20s to mid-30s with an expected weighted average life between two and five years. Category (b) includes Burford’s balance sheet participations in one of its funds (Burford has its own capital invested in certain of the funds it manages). Currently, this category comprises entirely of the Company’s portion in the Burford Strategic Value fund. In this category, it targets risk-adjusted IRRs in the mid-to-high teens with an expected weighted average life of one year or less. BUR uses its balance sheet to provide capital for higher-risk, higher-return, longer-lived assets, mostly those from the legal finance business, while it uses dedicated funds to invest in lower-risk, lower-return, shorter-lived assets that typify complex strategies activities, in which BUR acts as principal and acquire assets that it believes are mispriced and where value can be realized through recourse to litigation and regulatory processes. Merger appraisal situations are one key example.

For (2), BUR generates revenue and income from management fees and performance fees from its third-party asset management business. BUR uses the “European style” fee structure, meaning it only realizes its performance fees as the fund structure winds down. This creates economics of the fund management business that are back ended.

For (3), BUR earns fees generated for services provided by its asset recovery and legal risk management activities. This is the smallest segment and increasingly is a part of the business segment (1).

Capital provision constituted ~90% of total revenue in both 2019 and 2020, while asset management contributed ~7%.

Portfolio Mix

Burford has a very diversified portfolio. The charts below break down group-wide capital provision-direct commitments in four main categories, client type, geography, case types, and client industry.

Durability: Reasons for Using Litigation Finance

Litigation finance serves a critical function. Litigations are expensive and the outcomes are uncertain. At the same time, law firms prefer getting charged by the hour. This means, for the plaintiffs, the expenses are certain and high, while the rewards might be higher but uncertain. The economics of litigation thus deter plaintiffs from bringing about the lawsuits. This is where litigation finance comes into play. It allows the plaintiffs to offload the risks of litigation to a capital provider. For law firms, litigation finance allows them to obtain cash on an ongoing basis and pay their lawyers even when they have taken on a case on a contingent fee basis. When Burford first started its business, its focus was to engage with law firms. But increasingly, it works directly with corporate clients. (As of June 30, 2021, 58% of its assets are tied to corporates) It allows corporate clients to hire law firms that will only work on an hourly fee basis. Moreover, utilizing Burford’s services allows corporate clients to avoid incurring legal expenses as an operating expense. And if they have outstanding claims from certain lawsuits, they can monetize them by engaging with Burford. Litigation finance providers with adequate capital can construct a diversified portfolio to take on litigation risks and get compensated handsomely. The result is a win-win-win situation.

Importantly, there are no alternatives from mainstream financing sources. The legal knowledge required to underwrite investments in this area presents a high hurdle for traditional lenders to enter this field and the potential outcome of a successful case cannot be used as collateral to raise debt financing. Specialized litigation finance providers should continue to dominate this niche.

Moat

To be successful in litigation finance, you need access to three key elements: (1) relationships with law firms, (2) capital, and (3) talents/underwriting capabilities. To accumulate any of the three, time and experience are critical.

For instance, the sales process of litigation finance usually starts with RFPs from law firms on behalf of plaintiffs. Since the plaintiffs do not generally have enough knowledge of the industry to choose the provider, law firms are heavily involved in the decision to use litigation finance and the selection of the provider. Furthermore, to retain attorney work product protection, the plaintiffs tend to only invite a few parties to access their information. As such, the RFP process in litigation finance normally doesn’t exceed four bidders. Building close relationships with law firms, having demonstrated that you are a good partner to go through the litigation process with and that you would stick with them to the end of the process, etc. are therefore important to increase the odds of winning a financing deal without sacrificing excessively on the economics. And Burford has a highly reputable in this industry. Feedback from law firms suggested that they would advise client to choose Burford even when the economics for the client is 5-10% worse. The more deals you have done, the more relationships you have created. This then leads to easier and boarder access to deals going forward.

Capital, or fund raising, is also relationship dependent. The largest litigation finance providers, by definition, have the most extensive relationships with capital providers in the industry. They have both the time and track records on which trust with the asset allocator was built. Having at least $50 million in capital is critical. You need proper diversification to have staying power in this business since each financing deal produces all-or-nothing results and uncertainty persists in litigation. Having adequate diversification and capital base helps convince the client that you will be able to provide the capital needed no matter what happens in the litigation process or however long it takes to reach a conclusion.

With stronger deal pipelines and capital bases, these top-tier players can attract the best talents. Given the desire to learn and earn the best possible income, talents are generally attracted by the notion of joining a firm with the best existing talents. And with the best talents, these firms have higher likelihoods of achieving the best returns.

Hence, a positive feedback loop is formed: More relationships engender more deals, allowing the selection of the best deals. Great deals lead to better performance, which in turn attracts more capital. With more capital, talents can be better compensated and thus the best talents would be attracted and retained. And finally, with better talents, better deals and performance can be attained.

Competitive Landscape

Burford mainly faces two types of competitors: (i) Other pureplay litigation financing companies and (ii) multi-strategy alternative asset managers.

In group (i), Burford is by far the largest player. Importantly, not only does it have the most capital committed to legal assets, but it also has the largest balance sheet operation. This means it has the most amount of certain capital for potential commitments. Omni Bridgeway is one of the most prominent competitors. It currently manages $2.4 billion, and it is implementing a transition toward a fund management model fully by FY2024. Litigation Capital Management is another major competitor, but it is much smaller with only $336 million in asset under management. Size confers a lot of advantages in this business as clients want secured funding and do not want to be an outsized position for the funder. And certain complex deals can only be funded if the funder has a large enough pool of capital.

Group (ii) mostly refers to multi-strategy alternative asset managers who are entering this field as they seek more sources of investment returns. In 2020, Elliot Management, for example, financed the Eko’s patent lawsuit against Quibi, the now defunct streaming service founded by entertainment veteran Jeffrey Katzenberg. While these firms tend to have a lot more capital, they usually do not have the legal and litigation finance underwriting expertise inhouse. Instead, they will outsource such needs to other law firms. This means the plaintiff who engages a hedge fund in financing its lawsuit would need to share its sensitive information to more parties, incurring more risks of leaking such information. Moreover, most hedge funds do not have the right capital base to conduct litigation finance. Hedge funds with their quarterly redemption preference will face an asset and liability mismatch if most of their assets are in litigation finance, which has a life cycle of at least a few years.

It is important to note that I believe direct competition among the major players is not high and will remain muted in the medium term. First, the penetration rate of this market remains low, estimated at 5-10%. As an upshot, the focus of market participants is to grow the market and increase awareness of the services they provide. Second, this will not be a winner-take-all industry as incremental cost of scaling cannot be reduced to near zero. Even though operating leverage exists in litigation finance, it is not as strong as that in regular asset management. This is because the number of legal cases that require tens of millions in financing is limited. Hence the scalability per each litigation finance underwriter is also limited. Third, customer relationships tend to be sticky in this business. Burford mentioned that 70-75% of clients come back to them for more deals.

Quality

The quality of a business is determined by the return on invested capital it produces. For an investment business, this refers to the investment returns it can generate. Let’s examine Burford’s historical performance first.

Since inception, Burford has generated ~95% cumulative returns of its invested capital. Since the legal cases Burford invested in have an average duration of 2-3 years, this translates into an IRR of 30%. (Here it is of import to note that Burford structures its cases in a way that allows it to maintain its IRR even if the case takes longer to resolve)

The underlying return profile showcases a fat-tailed distribution. For instance, from 2012 to 2019, 4 cases produced ~66% of Burford’s net realized gains. While Muddy Water pointed to this as a reason for concern, this is instead the strength of the model. Litigation finance follows the return characteristics of all equity investing: asymmetric returns that favor the upside. As clearly demonstrated below, as expected, Burford has lost 100% of its money in some cases, while it made 8x the invested capital in other cases. Crucially, Burford has had many more “multi-bagger” than total losers. This inevitably means that investment returns of Burford fluctuate and are difficult to predict on a yearly basis. But over time, returns have been very strong.

One ongoing concern about litigation finance is that returns will deteriorate as time goes by (with more competition entering the space) and as the size of the firm increases. Both of these two concerns have not been observed so far at Burford. And as shown below, returns from recent years’ cohorts have been increasing and larger commitment deals have demonstrated stronger returns. I would argue that as Burford increases in size and focus more resources on deals that require larger commitments, the competition it faces declines. There are only two to three sizable players in the field that can commit more than $20 million in one case. This confers greater bargaining power to the litigation financiers. (However, there are some offsetting factors. For huge litigation cases that might bring about sizable rewards, some law firms are willing to take the case on a contingency basis, removing the need for litigation finance)

I discuss my expectation for future returns in the next section. But let’s examine the accounting policy and quality of earnings at Burford before we move on.

The 30% IRR since inception mentioned earlier is calculated from cases that are concluded since the Company’s inception. For cases that are concluded there is limited room for management to massage the numbers. But Burford has a policy that allows it to adjust the holding value of its litigation assets toward its estimated fair values even as the cases remain outstanding. Muddy Waters previously criticized Burford’s fair value adjustment policy. My assessment is that Muddy Waters’ concerns were invalid.

Burford’s accounting policy: Burford first books its investments based on the amount of capital invested, i.e. based on costs. Only when there is an objective event that occurs will Burford adjust the valuation of assets on its balance sheet. Such objective events include (i) a significant positive ruling or other objective event but where there is not yet a trial court judgment, (ii) a favorable trial court judgment, (iii) a favorable judgment on the first appeal, (iv) the exhaustion of as-of-right appeals, (v) in arbitration cases, where there are limited opportunities for appeal, issuance of a tribunal award, and (vi) an objective negative event at various stages in a litigation. And a case is only considered to be concluded when there are no longer any litigation risks remaining. While in theory the above gives room for management to manipulate asset valuation and hence earnings, the track record of Burford shows management has erred on the side of caution. First, since inception to 2019, only a minority of cases, 34%, had any fair value increase adjustments. Second, these are modest changes, with the average fair value increase at $5 million and the median at $2 million. Third, historical data demonstrates that Burford is more aggressive in recognizing fair value losses than fair value gains. The following tables shows fair value adjustments for concluded cases since inception to 2019. Only 33% of profits on successful cases were taken as fair value gains, while 47% of losses taken as fair value write downs.

As outsiders, we have no access to information regarding each litigation case Burford is involved in since it is under a strict obligation to protect the sensitive information it received. The underwriting process is therefore a black box to investors. And we can only trust management regarding its fair value adjustments. Given points discussed above, I believe the management of Burford deserves investors’ trust.

Finally, I would also like to highlight the efficiency of Burford’s operation. In FY2020, Burford employed 133 employees, of which 60 are lawyers. Including share-based payments, it incurred staff expenses of $62 million, or $466k per employee. The main competitor, Omni Bridgeway, employed 180 permanent staff and incurred staff expenses of $41 million, or $227k per employee. As such, Burford’s staff costs twice as much. On the other hand, Burford manages nearly twice as much in total assets. Asset managed per employee is twice as much at Burford than in Omni Bridgeway. This should allow Burford to incur higher level of margins than its main competitor despite higher per employee costs. Burford also does not capitalize its operating expenses as Omni Bridgeway does for some of its expenses.

Growth

Let’s first define the market size more granularly. Globally, the total legal service market is estimated at more than $600 billion. However, only around 30-40% of it is related to litigation. How much of this market will use litigation finance is anyone’s guess. Omni Bridgeway estimated that 40-50% of the litigation related legal market could eventually use litigation finance. This translates to an estimated global TAM of litigation finance of $90-100 billion, 65% of which from the U.S. Numbers below are in AUD.

Using the above assumptions, Burford currently has a penetration of around 4% ($4 billion invested capital out of a global TAM of $100 billion)

Historically, the industry has grown at a rapid clip. For instance, this industry in the U.S. was basically nonexistent before the Global Financial Crisis. Currently industry AUM in the U.S. stands at roughly $10 billion. While I do not expect the industry to continue its rapid growth rate of 30-40% p.a., I believe there is room for healthy growth of 20-30% over the next decade. For example, if the $10 billion U.S. AUM grew 25% p.a. over the next decade, it will still only amount to $75 billion by 2031. Due to limited scalability, one could argue that Burford cannot grow as fast as the overall market over the next decade. Even so, it is not a stretch to believe that Burford can grow its capital base by 20% p.a.

I performed the following sensitivity analysis to assess the range of reasonableness for growth expectation on Burford, using its relative size to total litigation finance assets in the U.S. as a measuring stick. Numbers that I deem reasonable are highlighted in green in the table below.

If the U.S. market does grow at 25% p.a. and Burford only at 20% p.a., its size relative to the U.S. market will drop from the current 40% to 28% a decade later, reaching $20 billion. I think this number is reasonable. If the global TAM grows at just an annual rate of 5%, representing global economic growth and growing usage of litigation finance, it will reach $142 billion by 2031. With $20 billion in asset, Burford will only have 13% of the overall addressable market, up from the current estimated 4%.

Management and Capital Allocation

Burford’s top management team previously suffered reputational damages from Muddy Waters’ accusations ranging from misrepresentation of financials and poor corporate governance (the former CFO of Burford is the wife of Christopher Bogart, the CEO of Burford). But with subsequent responses to the short allegations, the change in CFO, and a listing in NYSE, I believe most of the market concerns are alleviated already. Burford’s management was also thought of as being too promotional. But in my opinion, I think this has been more beneficial than harmful to Burford. While Burford is not the first mover into litigation finance, it is wildly considered the company that has popularized this product, and Christopher Bogart has been the key instigator of this trend. Furthermore, Burford is also known as an innovator in the field, pioneering new solutions, such as portfolio financing. There is also alignment of interests as the co-founders Christopher Bogart and Jonathan Molot each owns ~4% of Burford. My primary calls with ex-employees at Burford overwhelmingly highlight the high praises given to the top management team.

In terms of capital allocation, it is straightforward. Burford pays a nominal dividend, with the bulk of the cash flows reinvested into the litigation cases. Given the historical and target IRR of 30%, this has been the correct decision. Burford skipped its dividend payment in 2020 to preserve cash given the COVID uncertainty but has since reinstated it, distributing just under $30 million in dividends a year.

Since its listing, Burford has raised equity capital twice, $227 million in 2010 and $250 million in 2018, for a total of $477 million. On the debt side, it has raised $1.1 billion. Burford remains conservatively financed. Its net debt currently stands at $588 million. This is against a total equity of $1.6 billion. So net debt to equity is only 37%. Cost of debt is very manageable at 5-6%. Burford also does not have any asset liability mismatch. Weighted average life of debt stands at 5.1 years as of June 30, 2021, while the WAL of its litigation finance assets is less than 3 years.

Valuation

Valuing Burford is more challenging than valuing most other companies. The Company’s earnings fluctuate. It only has two public trading comps. Worse still, the comps either operates with a different focus (balance sheet vs fund operation) or is much smaller. However, as I show below, I think we can establish a range of estimated valuations that would highlight that Burford is worth more than its current market capitalization.

First, let’s consider the valuation of Burford’s competitors, Omni Bridgeway and Litigation Capital Management. The most straightforward way to compare the three players is EV/AUM. (This is not a perfect apple-to-apple comparison since Omni is transitioning toward a full fund management model, i.e. mostly third-party capital, while Burford’s asset base is still 64% its own assets) Omni has $1.7 billion in funds under management and an enterprise value of $900 million, for an EV/AUM multiple of 0.53x. LCM has $235 million in funds under management and an enterprise value of $147.5 million, for an EV/AUM multiple of 0.63x. If we apply the midpoint of these two multiples to the funds under management of Burford, we will get to $2.5 billion in enterprise value ($4.5 billion x 0.55), roughly where Burford is currently trading. I would argue this is the floor for Burford’s valuation. First, the vast majority of Omni’s business is now conducted through third-party capital. And a dollar of third-party capital under management is worth much less than a dollar of your own capital. Second, LCM is less than 5% the size of Burford. If we instead apply 0.7x to 0.8x EV/AUM to Burford, its enterprise value would be $3.2 billion to $3.6 billion, 20% to 35% above the current level. (Burford has net debt, so the equity value difference would be higher)

Next, we examine the earning power of Burford. To be conservative, we focus just on Burford’s own asset base of $3 billion. Let’s further assume Burford will only generate 15% of IRR on its asset base going forward. This equates to annual income of ~$450 million. Burford spends ~$100 million in operating expenses. As such, the “EBIT” power of the business should be closer to $350 million. If we capitalize it at 10x to 12x, we get enterprise value for Burford at $3.5 billion to $4.2 billion, 30% to 57% above the current level. This ignores the management and performance fees to be generated from the fund management busines.

Finally, we can also value Burford based on a multiple of book value. As of Jun 30, 2021, Burford has a net asset value of $1.6 billion, or $7.3 per share. Since listed, Burford has compounded its book value per share at 15% p.a. If we measure book value per share growth up to end of 2020 to eliminate intra-year balance sheet movements, the compound rate is 17%. If we assume 25% IRR of the investment portfolio, this will translate into an estimated book value compound rate of 14% using the same historical conversion rate of ~60% from portfolio IRR to book value compound rate. One can purchase an asset that compounds at 14% p.a. at 1.5x book value and sell it at 1.1x a decade later to still earn 9% annualized return. I believe Burford’s fair market cap is at least 1.5x book value, and that would be 15% above its current valuation.

Optionality that is Worth Nearly the Whole Market Capitalization

None of the above considers the pending lawsuit decision on YPF and the potential proceeds from the case. YPF is most successful litigation finance case in Burford’s history. It financed the lawsuits brought about by two Spanish companies and U.S. based hedge fund Eton Park against the Argentina government on the renationalization of the energy conglomerate, YPF. The plaintiffs are seeking damages from the Argentina government since their holdings were not acquired as part of the renationalization even though a tender offer rule was triggered. The plaintiffs together owned 28% of YPF before the renationalization. From 2016 to 2019, Burford sold part of its YPF assets for cash in a series of third-party transactions. The remaining YPF’s related assets are currently valued at $773 million on the balance sheet. This is understated. I estimate that the par value of the plaintiffs’ shares is $4.9 billion to $7.3 billion, adjusted for the portion Burford already sold. In another related lawsuit, the plaintiff received fifty cents on the dollar. If we use the mid-point of $6.1 billion as the par value, then Burford could expect a payout of $3 billion from its YPF assets that are currently valued at only $775 million on the balance sheet. This would give Burford an unrealized gain of $2.2 billion. The case is being heard in the New York courts, where interest rate is usually set at 9%. As the expropriation happened in 2012, interests would roughly double the damages. The case is expected to go to trial in May 2022. If Burford wins this deal, the proceeds from YPF would cover the majority of the current market valuation of the Company.

Risks and Misjudgment

Deteriorating Underwriting Standards

The underwriting of legal cases requires highly specialized skills, so does the valuation of such assets. The litigation assets are listed as “Level 3 assets” on the balance sheet. And outside investors have no means to verify such valuations themselves. As I mentioned above, historical valuations have proven to be reasonable and conservative. This has given me confidence in management’s team integrity and ability. However, there is no guarantee that this must remain the case. Investors must continue to monitor asset revaluation activities and potential write-downs vigilantly.

Regulatory Risks

There have been conversations on increasing transparency of usage of litigation finance in lawsuits. Some states in the U.S., such as Wisconsin, have already passed laws mandating such disclosure. One concern this potential regulation poses is that it might impact demand for litigation financing. Moreover, this might be a harbinger for more regulations directly targeting litigation funders. However, in most industries, an increase in compliance and regulatory complexity tends to favour the largest players as they have better economies of scale to shoulder the increase in operating costs. I believe any increased regulatory intervention to be a short-term negative but long-term positive for Burford Capital.